Text: Polina Tyutina

Photo: Alamy / Legion Media, sothebys.com, shutterstock.com

Art historian Polina Pavlovich in her lecture at the State Historical Museum in Moscow made a great introduction to Art Deco. With her permission Alrosa gives a brief extract of it.

Art Deco jewelry typically features elements that take us back to the great historical events and social transformations of the 1920s. They survived World War I and the Spanish flu: the generation that acquired a taste for life, celebrating its renewal and grandeur. France dominated the world of art; they reformed the system, focusing much of their energy on the collaboration between the state and artists, painters, sculptors, and whatnot—in other words, people who today would have been called “designers”.

The decade ushered in the technological revolution, fast-paced as life itself, reaching the pinnacle in transportation between countries and cities. Women were feeling the change, too, what with the devastating losses of the war. More and more began working outside the home, driving a car, and having it all in general. Gone were the elaborate hairstyles, replaced instead with a short bob. Long dresses, forgotten, gathered dust in wardrobes, while women opted for more practical à la garçonne style garments.

Inspired by the daring era, artists created new art movements—Fauvism, Cubism, Surrealism. The Roaring 20s also revolutionized the motion picture industry and jazz. All of these heavily influenced applied arts.

THE ZIG ZAG STYLE, INDUSTRIAL, CONTEMPORARY, MODERN. THAT IS WHAT THEY CALLED ART DECO BACK IN THE FIRST HALF OF THE 20TH CENTURY. THE NAME WE ALL KNOW WAS DERIVED IN 1966 FROM THE EXPOSITION INTERNATIONALE DES ARTS DÉCORATIFS ET INDUSTRIELS MODERNES HELD IN 1925.

Features

Art Deco is best defined by its geometric, contrast, and flat patterns, reflected in every original Art Deco jewelry piece.

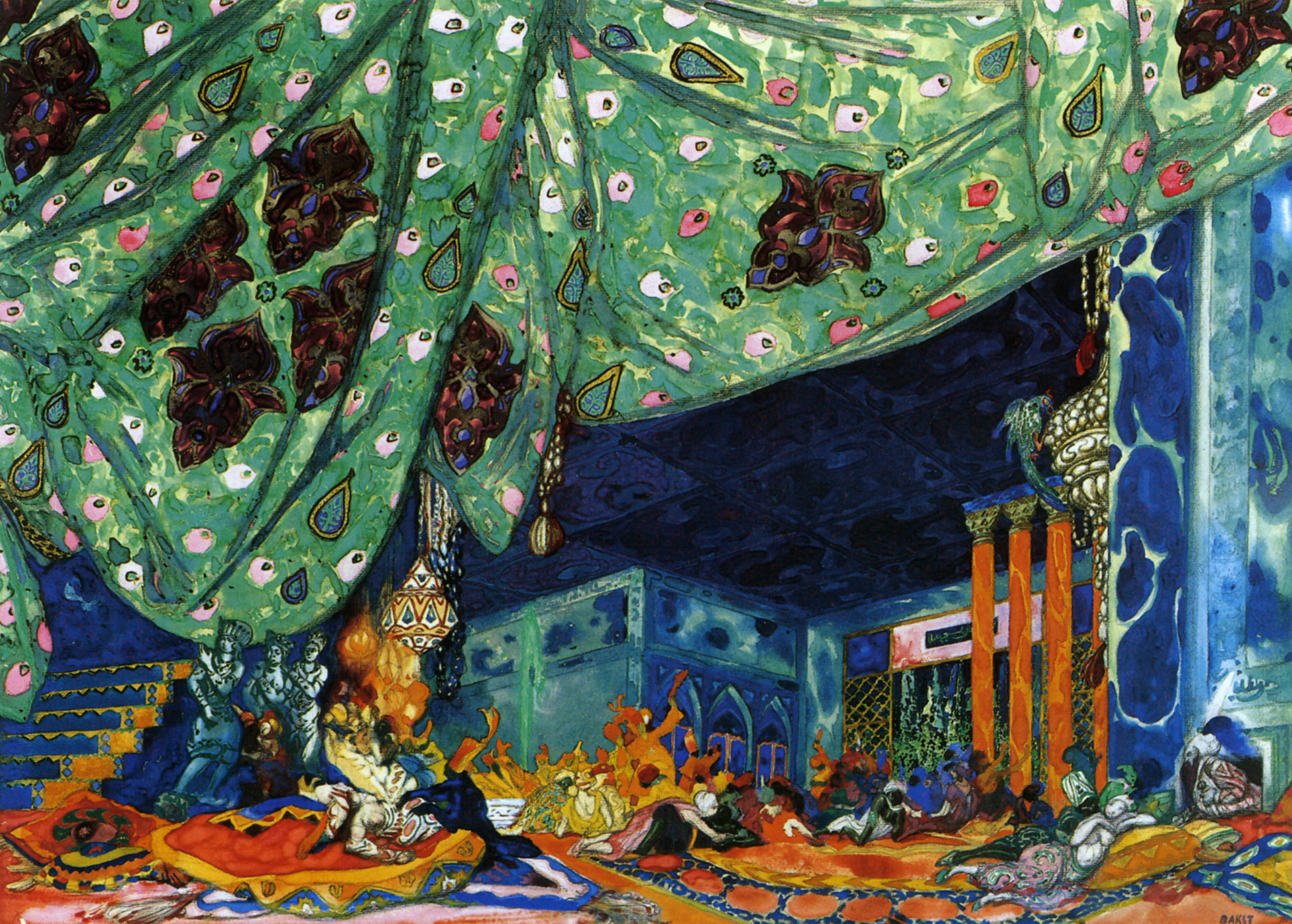

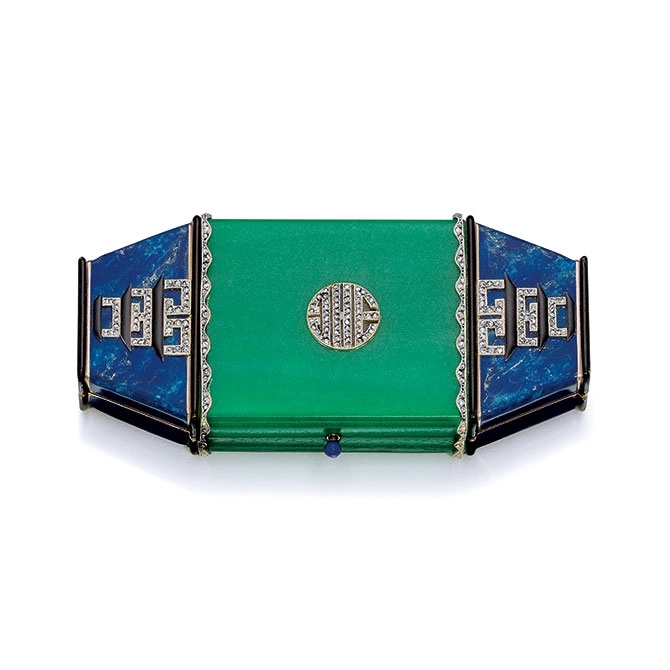

“Art Deco had its heyday in the 1920s, just as Sergei Diaghilev was introducing his aesthetic with the Ballets Russes,” says Polina Pavlovich. The Ballets Russes revolutionized ballet and changed the landscape of fashion. Léon Bakst was celebrated for his innovative costume design, richly decorated with lavish rhinestones, transparent fabrics, lurex, and oriental motifs. People got obsessed with the exotic and opulent designs of the Ballets Russes. “Parisians were caught up in the Bakst frenzy.” Bakst’s color orchestration of blue and green set apart his sceneries, this juxtaposition being something the fashion world had yet to have seen before. Art Deco embraced Bakst’s color patterns, placing deep green emeralds next to blue sapphires.

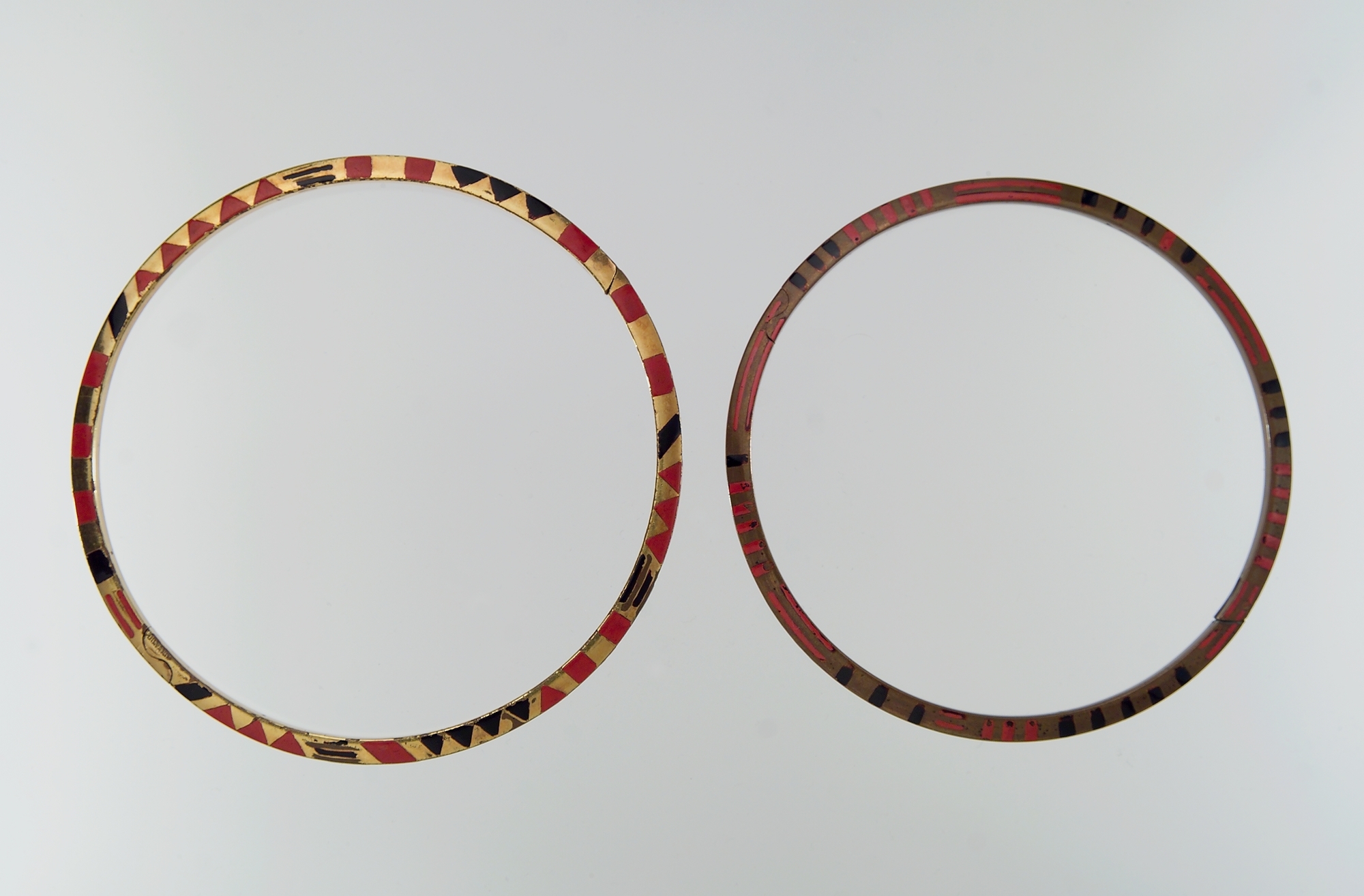

The artists became heavily fascinated with the Ancient Egyptian character and incorporated it into their Art Deco oeuvre, especially flourishing after 1922, when the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun and its treasures sparked huge popular interest. Ancient Egyptian motifs became an integral part of Art Deco jewelry, some masters going so far as to use the actual artifacts in their pieces. Cartier seemed to have known it all along—they’d had a passion for acquiring a lot of authentic Egyptian artifacts (these were different times), along with colored stones, even before the revolutionary discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb. Polina calls them visionaries. As ancient Egyptian style became a fashion statement, Cartier awed the world with their Egyptian-Revival Faience and Jeweled Fan Brooch featuring diamonds and the bust of the goddess Sekhmet.

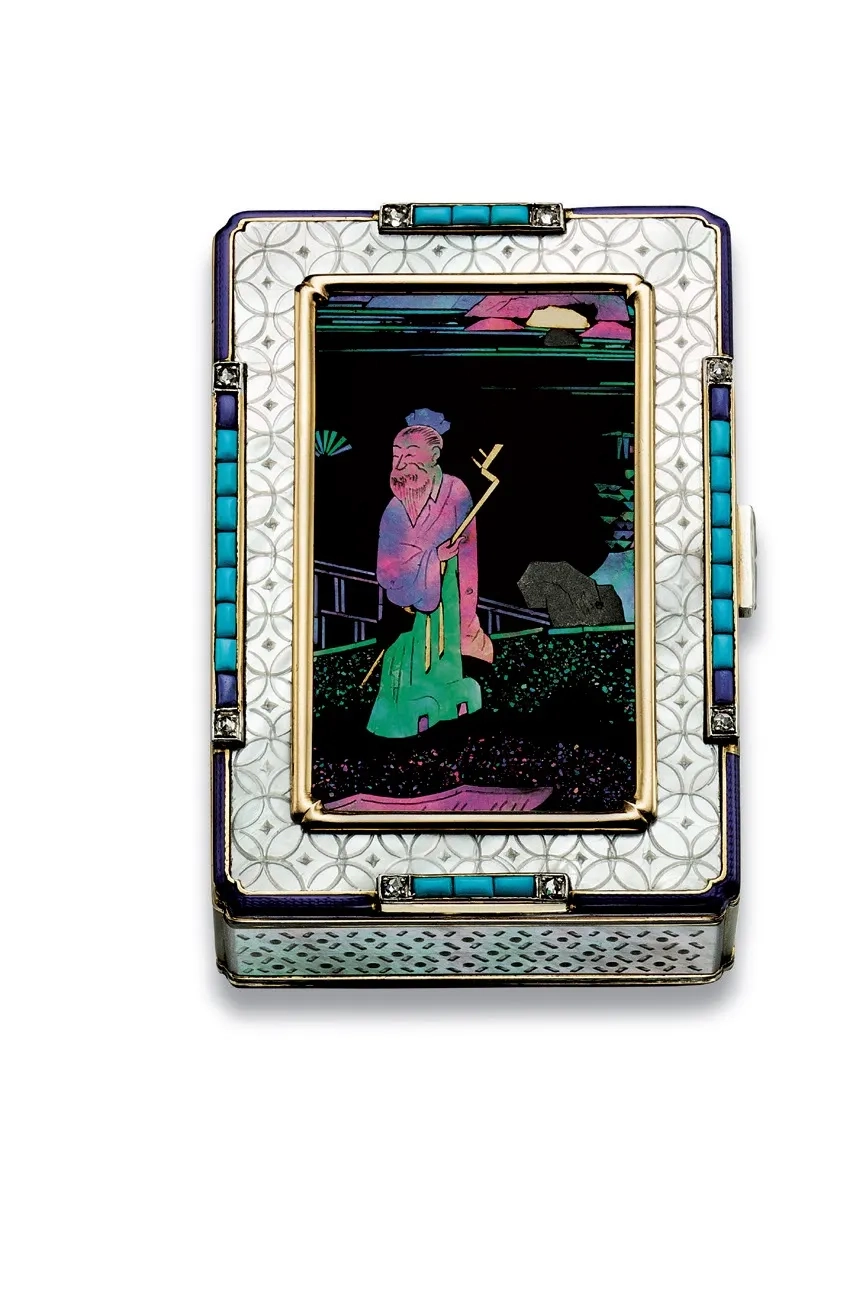

African and Oriental motifs all had some influence on the Art Deco jewelry of the 1920s. Jewelry makers drew inspiration from traditional Oriental designs, mixing their scenes with coral, lapis lazuli, and gemstone carving, the latter being a “distinctive feature of Russian and Oriental art,” according to Polina Pavlovich. “In the Russian Empire, Fabergé workmasters carved stones for French jewelers,” she adds.

Colored stones turned up extensively in Art Deco designs, mixed and juxtaposed to achieve and accentuate contrasts in color. Black onyx became the vogue because its deep color contrasted stunningly with other precious stones.

Cartier introduced a mix-and-match style that they nicknamed Tutti Frutti because of its resemblance to an Indian fruit salad. Sapphires, rubies, and emeralds defined the elaborate jewels, with onyx, diamond, and mother-of-pearl accents. The colored stones were often carved, and the motif was nature-themed, so they were shaped like fruits, berries, and flowers.

Art Deco also featured jade and coral, often the pièce de résistance in a collection. They tended to be carved or сut en cabochon, rather than cut and polished. “A combination of jade and coral in a piece of jewelry will most likely point to Art Deco,” the art historian says. Art Deco also goes hand in hand with crystal.

The 1920s brought with them monochrome styles, defined by a foray of jewelers into elaborate and intricate gem-cutting, showing off the new diamond cuts that sparkle most beautifully in artificial light—a gift of today. It is the star of the show everywhere it is taken, from restaurants to dance parties.

Platinum was the most often preferred metal of the era for jewelry purposes, particularly because it is neutral enough not to outshine the gemstone or alter the perceived color of the mineral. Platinum is a challenging metal to melt, and it was only “tamed” in the late 19th century.

Jewelers sought to make the metal invisible against the gems. Louis Cartier claimed that in order to achieve the mobility of the chain and the finesse of the fastening system, the jewelry house looked into train cars’ coupling. Van Cleef & Arpels pioneered their Mystery Setting, an invisible setting and an innovative jewelry-making technique.

Functional Jewelry

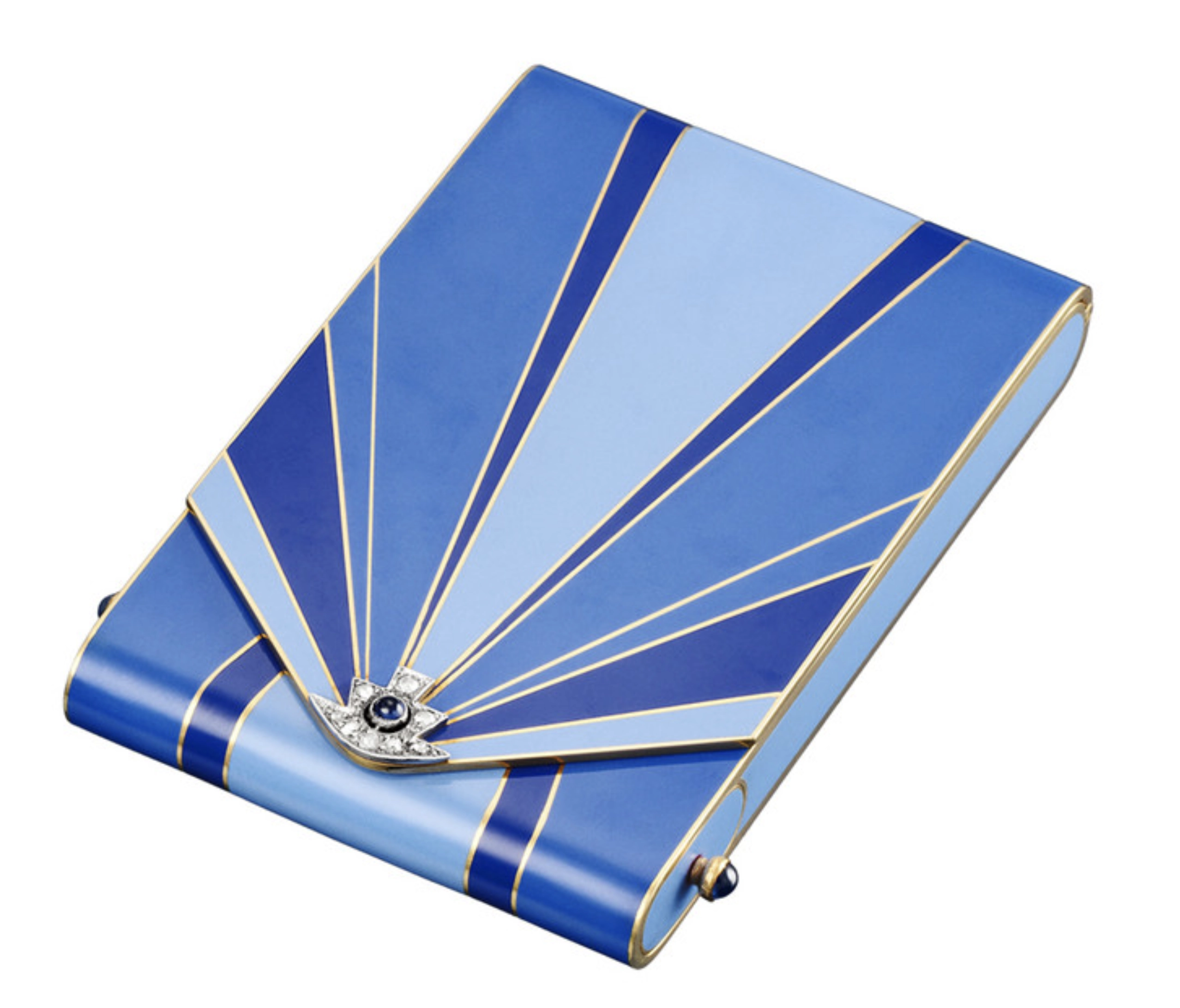

Art Deco artists married function and luxury in a versatile way. Women started making money, paying for themselves; they were eager to use make-up and could now touch it up wherever and whenever they wanted thanks to compacts. They also got into smoking. A make-up box or a minaudière kept the purse uncluttered and organized.

World War I saw a change in female smoking practices. Now, the sight of a woman smoking a cigarette was no longer a wonder but a common thing, and women wanted to look good doing it. So, cigarette cases and mouthpieces became fashion accessories, and as such were under scrupulous scrutiny by jewelers all over the Western world.

Jewelry that doubled up as other pieces was all the rage, for example, a dress clip, worn either as two separate clips, usually on the neckline of a dress and on the purse, or as two pieces affixed to one another to create a single, combined brooch. Necklaces also often had a convertible element to them, doubling as a bracelet, a brooch, etc., a tribute to the startling technological advancements of the 1920s that went beyond the heavy and automotive industries.

Fashionistas of the roaring twenties were all after sautoir necklaces, as those emphasized the more elongated silhouette, moving with steps and dance. They could be worn as traditional necklace pieces or over the shoulder, adding decoration to an exposed back in an open gown. Along with dangling long earrings, it drew attention to the beautiful feminine neck and sparkled as the woman moved. The earrings complemented fashionable short hairstyles because they allowed visibility to the ears and neck.

If you think of Art Deco, you’re likely to think of brooch pins, a shoutout to the Islamic culture all of Europe fell madly in love with. Women would wear a pin as a finishing touch on their suit jacket, with female wardrobes increasingly featuring suit sets.

A bandeau tiara came to replace an ordinary tiara in the 1920s. This glamorous head ornament resembled a jewelry ribbon embellished with gemstones, fixed firmly on the head during the foxtrot.

Wayward Jewelers

The roaring 20s also gave rise to jewelers who did not have a professional jewelry house background and designed pieces on their own, for example, Raymond Templier, Jean Fouquet, Gérard Sandoz, and Suzanne Belperron. Inspired in their creations by contemporary art, they were after more concise forms in the name of the avant-garde and all things extraordinary. They pioneered new aesthetics in jewelry, often seeking to juxtapose two different concepts. Suzanne Belperron, for example, designed crystal and hematite pieces. Cheap materials did nothing to lower the price of her jewelry, which is in great demand at auctions and from antique dealers.

Art Deco marked a time of discoveries and optimism for many jewelers and jewelry houses that forever went down in history for their one-of-a-kind revolutionary designs. A hundred years later, they are still the talk of the town, and so are their pieces, an eternal inspiration for architects, designers, and movie makers alike.